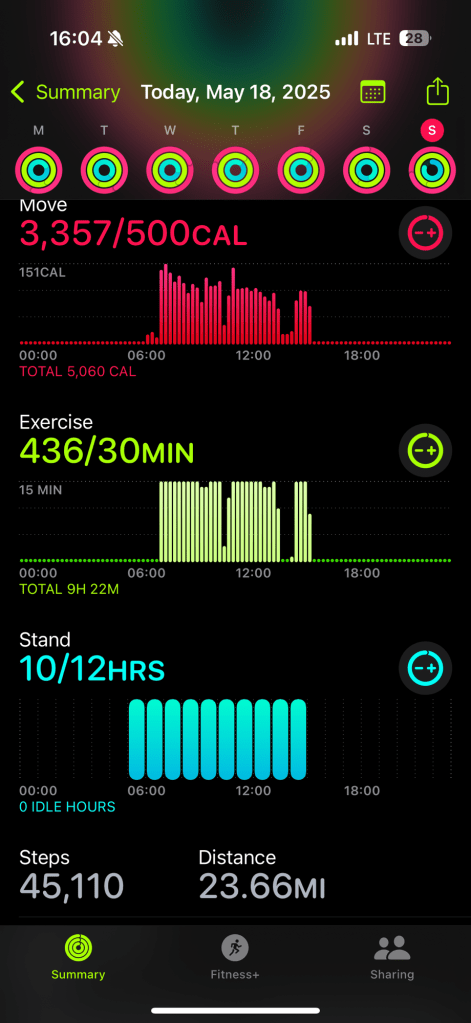

There’s a point in a long-distance backpacking trip where the novelty of the affair wears off and hiking begins to feel more like a job than a vacation. For me, this change hits at about the two-week mark. Not that I mind. Pushing through the boredom and monotony is type-two fun, and I’m, if anything, a type-two fun kind of guy. It’s just not good for journaling.

Now that I’ve excused my absence, the day’s hike from Leon to Astorga marked the end of the Maseta and the return to the mountains and hills. At this point in the hike, the terrain does not matter much to me. I’m more or less on autopilot for the rest of the summer.

It took me another nine days to reach Santiago. My notes from those days don’t include anything noteworthy, but there’s always the food.

When I travel anywhere outside the U.S., I always make it a point to sniff out a KFC. While it may sound like heresy for an American to eat American fast food abroad, I promise in this case it’s excusable.

KFC’s Zinger is one of the best-selling chicken sandwiches in the world. Probably second only to McDonalds’ McChicken. As best I can tell, they marinate the chicken breast in hot sauce and then bread it in the Colonel’s 11 herbs and spices. Add iceberg lettuce, mayo and a pedestrian burger bun, and you have one of the greatest creations to grace the face of the earth. And do you know the only country on earth where KFC doesn’t sell the Zinger? The United States of America.

Imagine my shock when I rolled into the Santiago mall food court only to discover that KFC no longer sells the Zinger in Spain. It was a terrible and heartbreaking end the hike.

The consolation prize was that I’d had one of the best pesto pasta dishes of my life a few day earlier in Portomarin. I’ll have dreams about that meal.

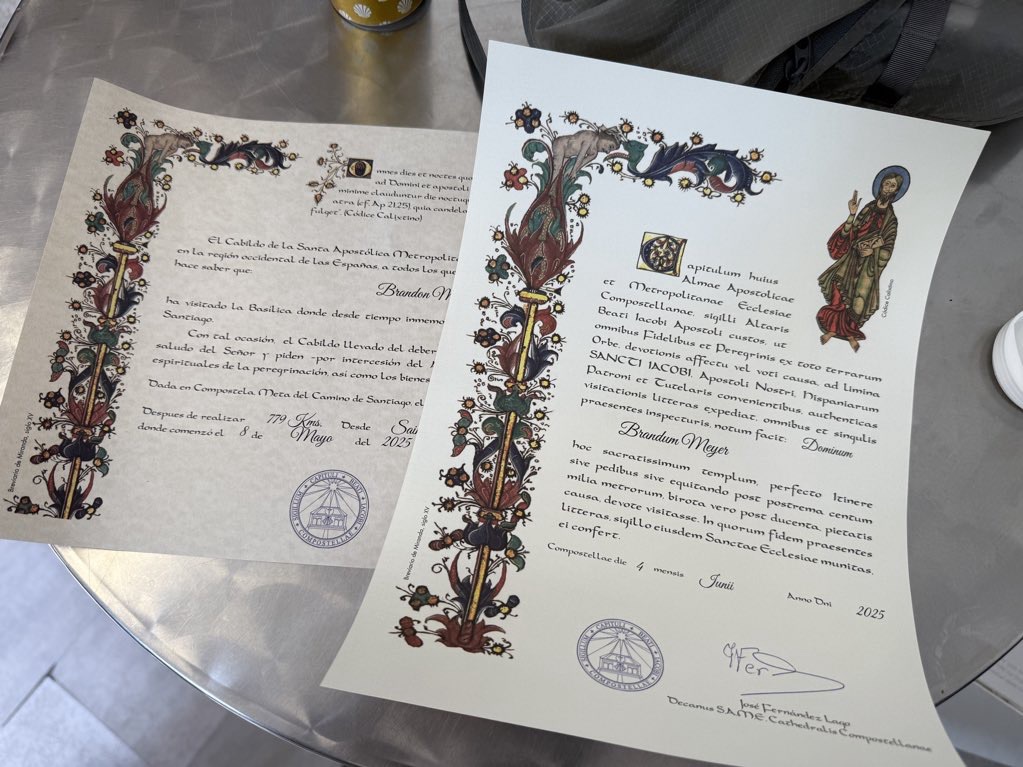

This visit to Santiago was about as unimpressive as it gets. After checking into the same hostel I’ve stayed at twice before, I took a shower, got a haircut, obtained my compostela from the pilgrim’s office and went to bed. I didn’t even make it to the church.

I slept through my 6 a.m. alarm leaving me just 30 minutes to pack my bag and run down the hill to catch my 7:45 a.m. train to San Sebastian.